I didn’t imagine that I would have the opportunity to go to Venice twice in one year, but this year I did; for Carnevale and the Architecture Biennale. As I arrived in Venice for Carnevale, I saw a blurry, grey city before me, and in that moment, Venice seemed to me to be the worst idea for a city ever. A floating city surrounded completely by water? Could that be a good idea?

On the last day, the only sunny day we had during Carnevale, I looked out towards Giudecca and felt a sudden pull, a sense that I didn’t really want to leave the city and that I had to come back. But also that it was, perhaps, in fact, a great idea for a city. Our future cities may need to deal with water, and what better example than Venice? I also wanted so much to find someone I could talk to immediately about our future cities and the future of our cities.

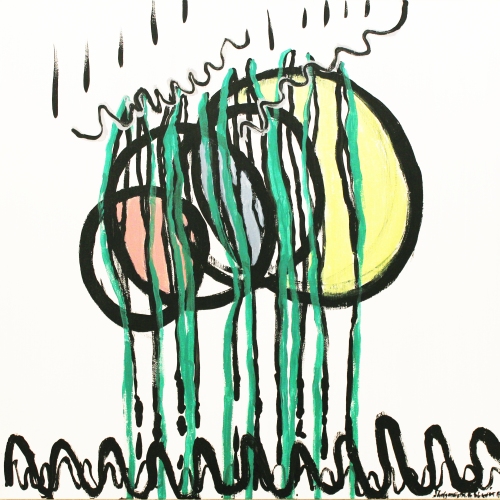

Carnevale 2, 5 & 21, Shaumyika SharmaVenice, May 2016, Shaumyika Sharma

Carnevale 2, 5 & 21, Shaumyika SharmaVenice, May 2016, Shaumyika Sharma

I didn’t have this opportunity immediately, but I did have it three months later. With my invite to the preview of the Architecture Biennale in hand, I packed my suitcase and got on a plane knowing I would experience a very different Venice. This time, I saw a sunny Venice, a warm Venice with long daylight hours, some mosquitoes and, it seemed, endless prosecco. I couldn’t believe it had taken me so long to go to a biennale, but I also felt that this was going to be an experience that would revive my deep love for architecture. It was kind of like a vow renewal to architecture.

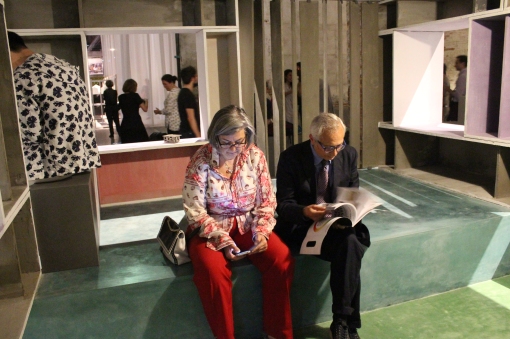

Arsenale, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

Arsenale, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

Through this sunny filter, I experienced a new wave of social engagement in architecture. Architects from all over the world reinforced our social purpose, a purpose that went beyond economy and means. This was the outcome of years of the industry struggling economically, a generation (or two) struggling to find purpose often without the traditional client, sometimes without construction, living with the irony that despite our ability to create stable structures, the foundations of our own industry appeared to be weak. A generation, my generation, now firmly understood that stability is perhaps a form of entitlement we may not know.

Renzo Piano (left, in blue) and Richard Rogers (right, in green), Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

Renzo Piano (left, in blue) and Richard Rogers (right, in green), Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

As architects, we are necessarily eternal optimists, however, and we seem to be finding our way towards a new form of practice, one that puts our social purpose front and centre, and lets the economy carry on.

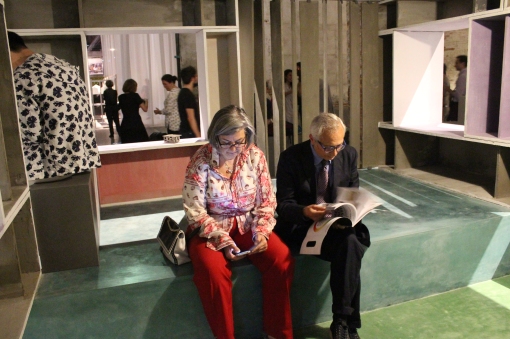

Irish Pavilion, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

Irish Pavilion, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

This is not to say that we can survive without economic means, but we have to think beyond the day to day. We have to think about everything we studied and everything we now know about cities, urbanism, poverty and disaster relief, the environment and climate change. All the lay-offs and salary cuts seem to have forced us to focus our attention elsewhere, to see the bigger picture, even as we struggled to ensure we kept roofs over our own heads. The economy has caused many to leave the profession, but it has resulted in the rest of us thinking about our roles as problem-solvers.

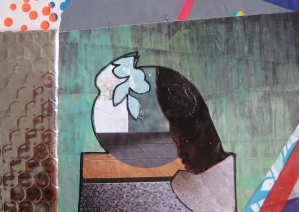

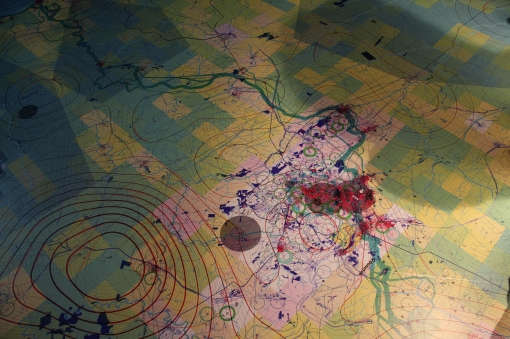

Architecture Ukraine: Beyond the Front, Biennale 2016 Collateral Event, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

Architecture Ukraine: Beyond the Front, Biennale 2016 Collateral Event, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

Suddenly, the hold that the economic collapse has had on our industry (and most other industries) seems almost unimportant. Although it has disrupted our lives, our livelihoods, our industry, it has not, as such, had an impact on our skills, our role in society, our capacity to improve people’s environments, and therefore their lives. Everyone needs to put food on the table, but our skills can solve problems that go far beyond this.

Still from film about the Kumbh Mela, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

Still from film about the Kumbh Mela, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

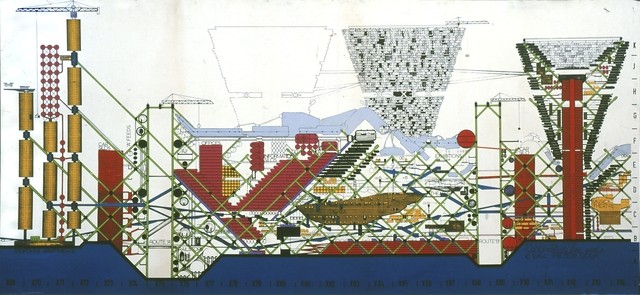

It’s hard to pinpoint any one pavilion or installation that summed up the Biennale’s theme of ‘Reporting from the Front’, but there are some highlights that will stay with me. The Kumbh Mela, a festival in India that takes place every 12 years, was presented as a prototype of rapid urbanism. At this festival, a city housing millions is built in a very short period of time, and dismantled just as quickly.

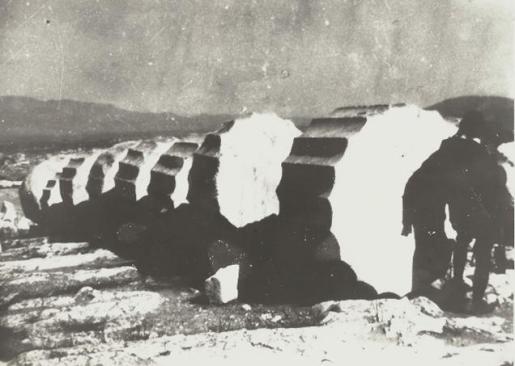

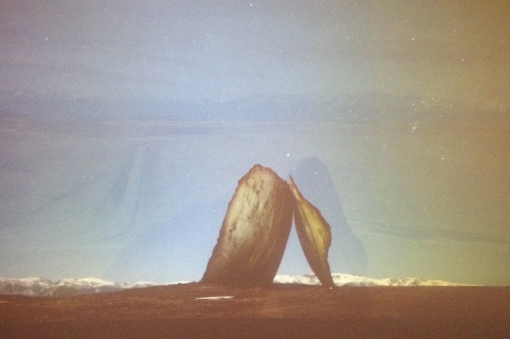

A film by Ensamble Studio turned construction into poetry in a way I had never seen.

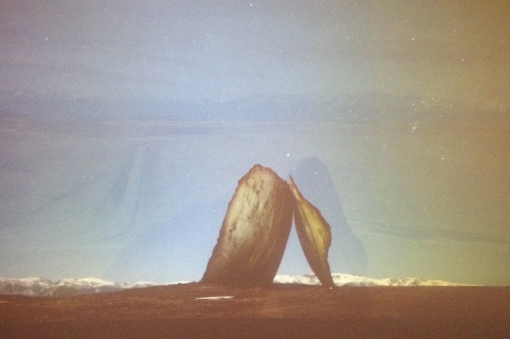

Stills from Ensamble Studio’s film, Biennale 2016, Shaumyika Sharma

Stills from Ensamble Studio’s film, Biennale 2016, Shaumyika Sharma

The Australian pavilion was brilliant for its simplicity and clarity. The pool was at the centre of the pavilion and overlaid with audio from a variety of Australian voices. The idea of the pool, or a body of water at the centre of our existence, is so quintessentially Australian. In modern Australian life, much of our time revolves around the pool, the beach, the sea, but also as a country with so much desert, the watering hole, the idea of finding water, has always been important to all inhabitants of the country.

Australian pavilion, Biennale 2016, Shaumyika Sharma

Australian pavilion, Biennale 2016, Shaumyika Sharma

Anupama Kundoo’s work in India, particularly her material experiments were a call for action to do things differently, to find solutions through materiality, using local materials and techniques to create affordable housing.

Anupama Kundoo, Material Experiments, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

Anupama Kundoo, Material Experiments, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

Anupama Kundoo, Affordable House Prototype, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

Anupama Kundoo, Affordable House Prototype, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

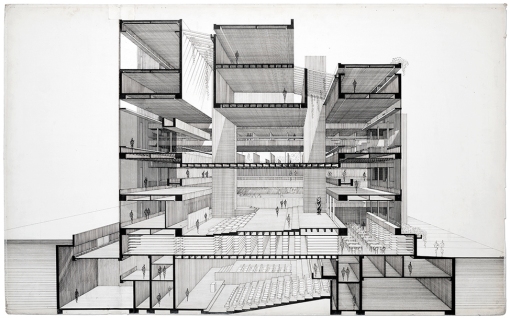

Similarly, the US pavilion’s ideas for Detroit included a very important series of experiments by T+E+A+M who re-used or upcycled trash and rubble to create new forms of construction material.

T+E+A+M’s installation, US pavilion, Biennale 2016, Shaumyika Sharma

T+E+A+M’s installation, US pavilion, Biennale 2016, Shaumyika Sharma

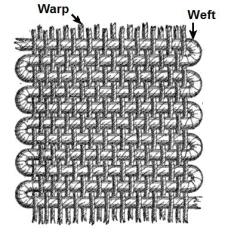

Peter Zumthor’s installation for which he collaborated with a textile designer was subtle and moving, and of special interest to my practice since we are currently working on a Weaver’s Co-op.

The work of Peter Zumthor with Christina Kim, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

The work of Peter Zumthor with Christina Kim, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

There were other related events including a Zaha Hadid retrospective, significant and awe-inspiring as the profession mourns her loss.

Zaha Hadid Retrospectice, Venice, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

Zaha Hadid Retrospectice, Venice, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

I also made time to see Tadao Ando’s Punta della Dogana , which was presented in ‘miniature’ form at the Biennale, but the real thing similarly inspired awe.

Punta della Dogana, Tadao Ando, Venice, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

Punta della Dogana, Tadao Ando, Venice, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

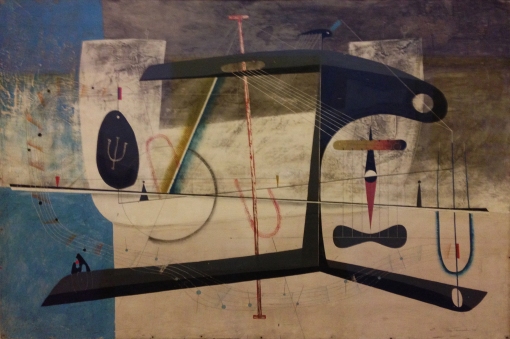

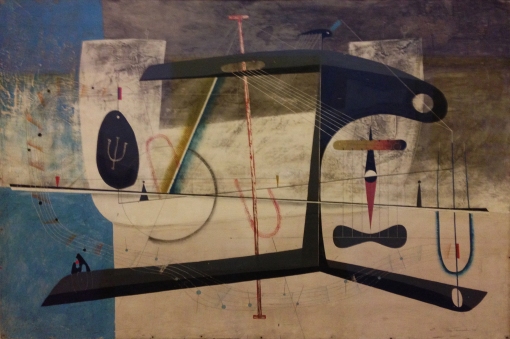

Of course, no trip to Venice would be complete without a visit to the Peggy Guggenheim Collection.

Psi, John Tunnard at the Peggy Guggenheim collection, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

The biennale filled my cup. It was fresh oxygen. I can sustain myself for years now. I left with the understanding that money is essential, but purpose is what keeps us going.

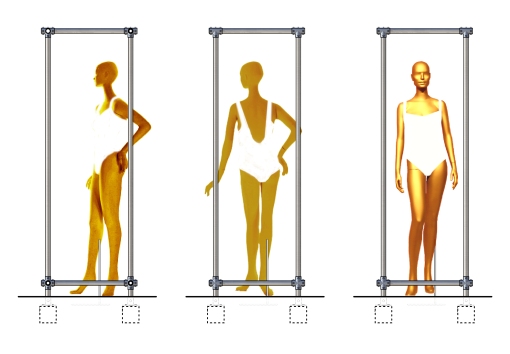

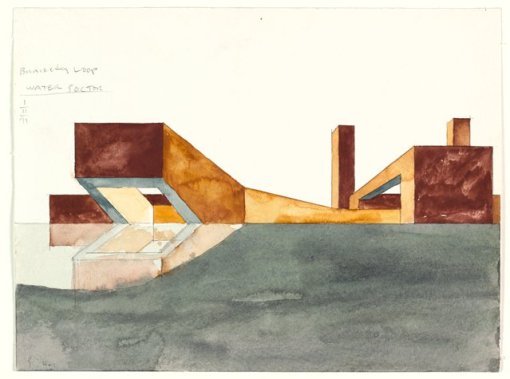

Bathers, Perspective View, Shaumyika Sharma

Bathers, Perspective View, Shaumyika Sharma Bathers, Perspective View, Shaumyika Sharma

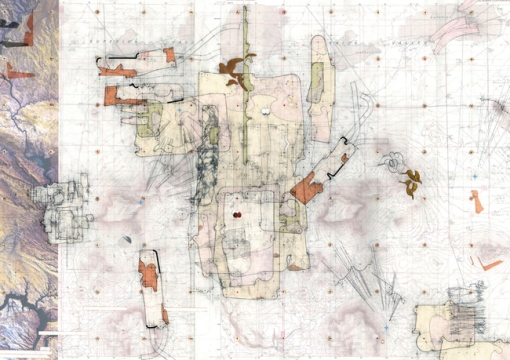

Bathers, Perspective View, Shaumyika Sharma Bathers, Detail Elevations, Shaumyika Sharma

Bathers, Detail Elevations, Shaumyika Sharma Bathers, Detail Model, Shaumyika Sharma

Bathers, Detail Model, Shaumyika Sharma Block Printing in Ranthambhore, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

Block Printing in Ranthambhore, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

Contemporary Indian Weaving Mill, image courtesy of The Textile Magazine

Contemporary Indian Weaving Mill, image courtesy of The Textile Magazine

Women making Quilts in Ranthambhore, image courtesy of Dastkar Ranthambhore [6]

Women making Quilts in Ranthambhore, image courtesy of Dastkar Ranthambhore [6]

The Varanasi Project, images courtesy of Nest [7]

The Varanasi Project, images courtesy of Nest [7] Kyoto Weaver’s Space, image courtesy of Hosoo [8]

Kyoto Weaver’s Space, image courtesy of Hosoo [8]

Carnevale 2, 5 & 21, Shaumyika SharmaVenice, May 2016, Shaumyika Sharma

Carnevale 2, 5 & 21, Shaumyika SharmaVenice, May 2016, Shaumyika Sharma Arsenale, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

Arsenale, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma Renzo Piano (left, in blue) and Richard Rogers (right, in green), Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

Renzo Piano (left, in blue) and Richard Rogers (right, in green), Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma Irish Pavilion, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

Irish Pavilion, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma Architecture Ukraine: Beyond the Front, Biennale 2016 Collateral Event, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

Architecture Ukraine: Beyond the Front, Biennale 2016 Collateral Event, photo by Shaumyika Sharma Still from film about the Kumbh Mela, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

Still from film about the Kumbh Mela, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma Stills from Ensamble Studio’s film, Biennale 2016, Shaumyika Sharma

Stills from Ensamble Studio’s film, Biennale 2016, Shaumyika Sharma Australian pavilion, Biennale 2016, Shaumyika Sharma

Australian pavilion, Biennale 2016, Shaumyika Sharma Anupama Kundoo, Material Experiments, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

Anupama Kundoo, Material Experiments, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma Anupama Kundoo, Affordable House Prototype, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

Anupama Kundoo, Affordable House Prototype, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

T+E+A+M’s installation, US pavilion, Biennale 2016, Shaumyika Sharma

T+E+A+M’s installation, US pavilion, Biennale 2016, Shaumyika Sharma The work of Peter Zumthor with Christina Kim, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

The work of Peter Zumthor with Christina Kim, Biennale 2016, photo by Shaumyika Sharma Zaha Hadid Retrospectice, Venice, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

Zaha Hadid Retrospectice, Venice, photo by Shaumyika Sharma Punta della Dogana, Tadao Ando, Venice, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

Punta della Dogana, Tadao Ando, Venice, photo by Shaumyika Sharma

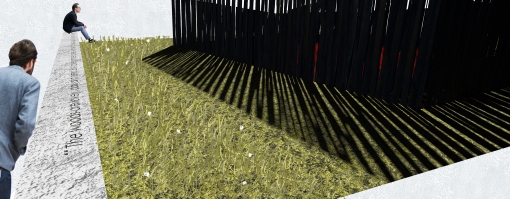

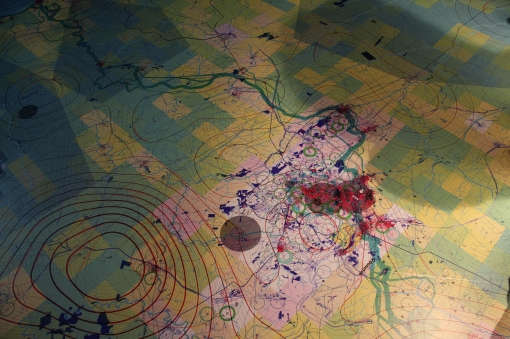

Three words from the famous Robert Frost poem Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening inspired this Poet’s Garden; lovely, dark and deep.

Three words from the famous Robert Frost poem Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening inspired this Poet’s Garden; lovely, dark and deep.  The experience of our Poet’s Garden is intended to be like a journey through woods. A path, semi-enclosed by dark stained ‘stick fencing’ slopes down gently into the depths of the earth such that the smell of soil becomes apparent. Frost’s poem is set in winter, but in summer our journey ends in the ‘lovely’ circular ‘field’ of red poppies at the heart of the scheme. Warhol’s and van Gogh’s The Poet’s Garden were also influences as were Reford Gardens’ own Himalayan blue poppies. The last four lines of Frost’s poem are engraved on a bench on the East side.

The experience of our Poet’s Garden is intended to be like a journey through woods. A path, semi-enclosed by dark stained ‘stick fencing’ slopes down gently into the depths of the earth such that the smell of soil becomes apparent. Frost’s poem is set in winter, but in summer our journey ends in the ‘lovely’ circular ‘field’ of red poppies at the heart of the scheme. Warhol’s and van Gogh’s The Poet’s Garden were also influences as were Reford Gardens’ own Himalayan blue poppies. The last four lines of Frost’s poem are engraved on a bench on the East side.  The garden has the potential to grow and evolve over time since poppies are self-seeding. As the poppies my perish in July, lavender is interspersed amongst them to prolong the enjoyment of flowers. In winter, the garden will more closely ‘resemble’ the poem. The wild-grass-covered open space could be used for events in the year(s) to come.

The garden has the potential to grow and evolve over time since poppies are self-seeding. As the poppies my perish in July, lavender is interspersed amongst them to prolong the enjoyment of flowers. In winter, the garden will more closely ‘resemble’ the poem. The wild-grass-covered open space could be used for events in the year(s) to come.